As a helicopter hovers near the steep, steaming cliffs of Waimangu Valley, a battle against invasive pampas grass is underway. Contracted by Bay of Plenty Regional Council, the helicopter is part of an aerial control operation targeting the pest plant, which at first glance can be mistaken for native toetoe.

Regional Council Land Management Officer Rob Ranger explains that pampas, originally from South America, spreads rapidly due to the thousands of wind-borne seeds it produces. “Ongoing control is essential to stop it establishing across the valley and on cliffs too dangerous to access on foot,” he says. “With traditional ground control methods ruled out, the only option is to use aerial spraying to apply a selective herbicide that targets pampas without harming the rare geothermal kānuka. This precision is vital, not just for safety, but for protecting the rest of the native species there.”

Rob Ranger

Waimangu is not just visually striking; it’s ecologically and culturally unique. The valley is home to geothermal vegetation found in few other places in Aotearoa, and nowhere else in the world. “The nationally endangered geothermal kānuka thrives in the harsh, exposed soils and is only found in the Taupō Volcanic Zone,” Rob explains. “Its presence or absence signals the health of the whole ecosystem. This particular type of kānuka stabilises fragile geothermal ground and provides habitat for native wildlife, but its survival is under pressure.”

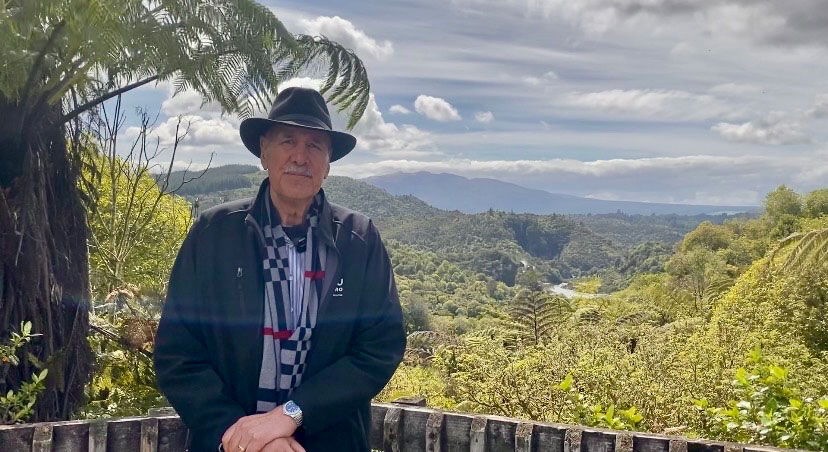

Rangitihi Pene

For Rangitihi Pene of Tūhourangi Ngāti Wāhiao, Waimangu holds deep ancestral importance. “The significance of Waimangu to our tribe is that it’s one of the few positives to come out of the Tarawera eruption – it was born on that day,” he says. “It still encapsulates all of the things that are considered taonga to our tribe – the geothermal features, the geysers, the beautiful lakes, and the strong link to one of the pink terraces.”

It’s these taonga that drive the vision Tūhourangi holds for the area explains Rangitihi. “We’ve always had the kaupapa, the philosophy, that we wanted to make Waimangu like a natural habitat again, to bring back our native birds and trees.”

The arrival of pampas grass threatens that vision. Unlike toetoe, which is valued for its use in making tukutuku panels and for insulating the walls and ceilings of wharenui, pampas looks the same but doesn’t have the same qualities. “It’s really just an imported pest,” laments Rangitihi.

Ken Raureti of Ngāti Rangitihi shares similar concerns and hopes for the future. “Our aspirations for Waimangu are ki te whakatū te taiao anō – to replenish, to give health and vibrance and life back to the valley. To bring the birdsong back. To let the valley come back to its oranga, to its wellness.”

Ken sees pampas as part of a wider ecological challenge that can’t be ignored. “I think of the invasions – pest invasions, weed invasions, wallabies, deer, wilding pines – things that don’t belong here. Kāore rātou i ora ai ki kōnei. Whilst they thrive here, they don’t belong here.”

Ken Raureti

He remembers when pampas first appeared. “We didn’t realise the threat it posed, but as it spread around the shores of our lake and started to dominate, we realised these are invaders to our territory. In the last few years, we’ve worked with the Regional Council to try and eradicate pampas, because it smothers the growth of native flora. It creates its own environment, and if we didn’t do anything, we’d have the land of pampas.”